Croatia and Slovenia stand out from other Balkan countries for their political organization and its relatively stable economy.

Zagreb, Croatia (December 20, 2011) .- Former Bosnian

Nedim Hadzic soldier could not imagine that would be one of the protagonists of one of the most brutal conflicts of the 20th century.When in 1995 the Serbian Yugoslav Army troops ended three long years of siege of the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo, thanks to the Dayton Peace Agreements, Hadzic was only 19 years old and terrible memories etched in your mind.

“So I lost my adolescence,” said the young Muslim Reform, which after the war left arms, began to study medicine and now in his spare time, works as a guide for travelers who want to see the sights of war. “It’s my way of exorcising demons.”

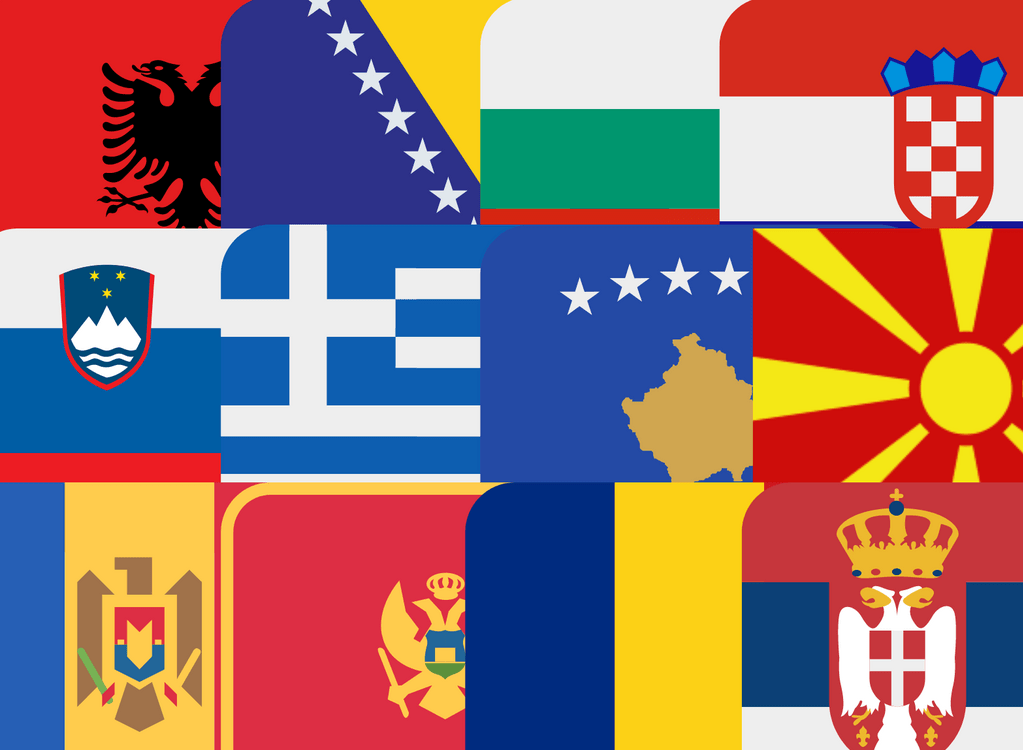

At 20 years of the beginning of the dissolution of Yugoslavia, which began with the independence of Slovenia in 1991, the traumas of the Balkan wars that led to the creation of seven new states are still there while the repairs to the neighbors even impossible for theregion is safe from political instability and ethnic tension.

“Most of the countries of the former socialist Yugoslavia are still wary of their neighbors and are reluctant to resolve past conflicts,” said English REFORM analyst Marcus Tanner.

Far from a definitive solution to the complex Balkan geopolitical map, only the Catholic Croatia, which is preparing to enter the European Union (EU) in 2013, and Slovenia, as it did in 2004, enjoyed a political organization and a relatively stable.

By contrast, the situation in Montenegro, which aims to become the Las Vegas of the Balkans, is more volatile, also is believed to be an important path of drugs to Europe. Still, the most distressing is that of Bosnia, a

country that lacks the last 13 months because the Government Muslims, Serbs and Croats do not reach an agreement.

Equally problematic is the tension between Serbia and Kosovo. The first refuses to recognize the independence of its former province and the latter is unable to give guarantees to the Serb minority, which has led to clashes in the north of the country and generated the EU refusal to allow the entry of Serbia.

However, Serbia and Kosovo yesterday reached an agreement to jointly manage the crossing points in northern Kosovo border issue in recent days that led to clashes between the Serb and NATO Force in Kosovo (KFOR).

Another is the reality of Macedonia, a country locked in an eternal dispute with Greece around his name and the paternity of Alexander the Great, where the conservative coalition in power is unable to resolve the conflict between the Slav majority and Albanian minority, while the unemployment reaches 30 percent of the population.

Bosnia, Macedonia and Kosovo are the most volatile areas of the region, the Serbian historian Chedomir Antic, a situation that refers to the interference of the EU and U.S., according to the expert.

“There is no doubt that without international interference, the situation in the Balkans would be far less complex and tense,” he told REFORM.

“In Bosnia, for example, which is not helping is the unconditional support of the U.S. Muslim nationalism and the EU. It is also something diametrically opposed to what they do in Iraq or Afghanistan, but who cares?” Questioned Antic.

Croatian experts as the Beskid Inoslav say that what has hurt the region is exacerbated nationalism and the endless territorial claims.